Gaelic: Taghan giuthais

In northern Scotland we are privileged to live close to, and occasionally see, one of the rarest native mammals found in Britain – the Pine marten. These beautiful animals are elusive, but they do leave us clues of their presence.

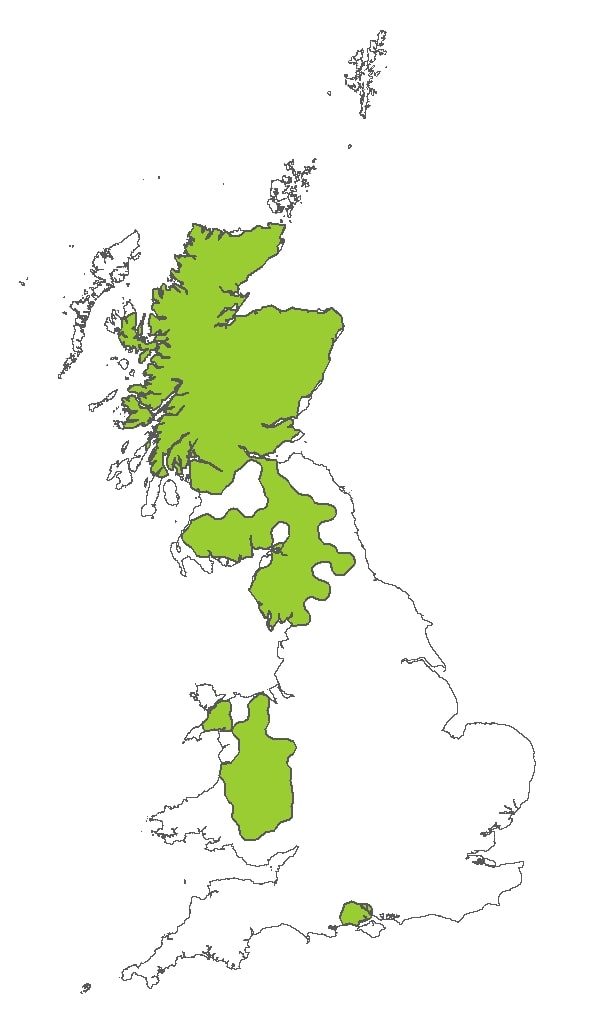

Distribution

Once widespread across the UK, by the 20th century hunting and woodland clearance had restricted pine martens to parts of the Scottish Highlands and tiny pockets of Wales and northern England. Now legally protected, numbers have increased in Scotland, and they now occur throughout the Highlands north of the Central Belt, and in the Scottish Borders. Martens remain very rare in England and Wales and populations have been boosted by translocating animals from Highland Scotland in a few areas.

When to Look

Pine martens are active all year so they, and their field signs, can be found at any time.

Where to look

Pine martens prefer woodland habitats, especially places with mature trees with holes and cavities that are used for shelter and breeding. However, martens can survive in more open country, like much of north Sutherland, provided there is some tree and scrub cover. They also have large territories (up to 25 square km), so a few martens go a long way!

What to look for

The Pine Marten

The pine marten has a long, lithe body and is similar in size to a small domestic cat. It has generally chocolate-brown fur and a pale-yellow patch, or bib, around its throat and chest. A thick more greyish-brown winter coat develops in September, and is moulted in April, giving a thin dark brown coat in summer. Pine martens have large, round ears outlined with paler fur, and a long, bushy tail. Adults are around 60–70cm long and weigh approximately 1–2kg. Males are roughly a third bigger than females.

Pine martens are in the mustelid (weasel) family and could be confused with some of their cousins – otter, polecat, American mink, weasel and stoat. Pine martens have longer legs and are much more likely to be seen in trees than any of these other species, especially otters! Weasels and stoats are a lot smaller than pine martens. American mink are usually smaller than pine marten, darker brown, with a white chin, and smaller ears. Polecat has a mask of pale fur above the eyes and around the mouth, small ears, and a blackish coat with a cream underfur that shows through. Mink and polecat are unlikely to be seen in northern Scotland.

Tracks and signs

Droppings, known as scats, are good clues to pine marten presence. Scats are used to mark territories and left in regular latrines, usually on boulders or logs that are conspicuous to other martens. These latrines are often conspicuous to us too – they are frequently found along forestry trails. When they’re fresh, scats are blackish and slimy, with a musty, sweetish smell. They are variable in size: 40-120mm long and 8-12mm thick. They may contain fur, feathers, bones and seeds.

Poop facts

Experts say pine marten poops smell floral, like damp hay or parma violets!

They have a distinctive ‘S-shaped’ from how pine martens ‘wiggle’ when pooping.

Bright red or blue scats in summer show a pine marten has been eating a lot of rowan berries or bilberries.

Pine marten scats can look like small fox droppings, and without a DNA test it can be tricky to tell the difference. Scent can be helpful as pine marten scats tend to have a musty sweet smell that is not unpleasant, whereas fox poo stinks!

(Please don’t get too close or touch any animal poop without gloves or a dog poo bag, and always wash your hands afterwards!).

Tracks

Pine marten footprints can sometimes be found in snow or mud. All mustelids have five toes, unlike dogs and foxes which have four. Prints are roughly 3.5cm wide and 4cm long, with a stride of 50-80cm.

Pictures of scats and footprints are available here: https://www.mammal.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Pine-marten-Field-Sign-Guide-PDF.pdf

Please send us details of any sightings or signs of pine martens.

Food

Pine martens mainly eat small mammals, such as voles, mice and squirrels, but can take prey up to the size of a hare. They will scavenge on carrion, take birds and eggs when they can, and fruit and berries are readily eaten too.

Grey squirrels are also on the menu for pine martens where they occur together. Research is showing that the presence of pine martens reduces the numbers of non-native grey squirrels and has a positive impact for native red squirrels. It seems grey squirrels don’t know about pine martens, as there aren’t any in North America where grey squirrels come from, so they aren’t afraid when they really should be!

Pine martens can be tempted to feed in gardens. The best foods to use are raw peanuts scattered on the ground or on a bird table, or peanut butter or jam smeared on a log.

Breeding

Pine marten pairs only meet up during the mating season, in the summer. Apparently, they make a shrill, cat-like ‘yowl’ during this period. Pine marten kits are normally born in March or April in dens in hollow trees or the fallen root masses of Scots pines. Cairns, cliffs and buildings are occasionally used for dens too. Kits emerge from the den when they are six weeks old and are fully grown at six months old. Pine martens normally breed for the first time at around 2–3 years old.

Conservation Status

Pine martens and their dens are fully protected by the Wildlife and Countryside Act (1981); martens must not be disturbed, killed, trapped, or sold, except under licence from NatureScot. Despite this legal protection, poisoned baits and traps, often set for hooded crows and foxes, still probably account for many marten deaths each year, and some are killed on roads.

- Big thank you to Alan West for photos and video of pine martens taken in his garden.