By Abby Rhodes

Introduction.

North Sutherland is home to the most northerly breeding barn owls in the world (Forrester et al., 2007, 2, 903). According to Vittery (1997) ‘in the nineteenth century [the barn owl] bred at Rosehall, in the north (Tongue) and the west (Loch Assynt)’, and he continues, ‘but there are no recent records for any of these areas’. However, an article in The Northern Times for 22nd June 2007 recorded the successful hatching of six chicks in Strathnaver, later ringed by Paul and Jenny Butterworth of Bettyhill.

My husband Gary and I moved to Sutherland, near Tongue, from Yorkshire in 2010, and my involvement with Barn Owls began when I started training to become a bird ringer in 2012 with the aforementioned Paul and Jenny Butterworth. During my training I gained experience handling and ringing chicks of various species, from willow warblers to white-tailed eagles.

My interest in the prey species of barn owls began in 2016, but I will start here in 2015, when I gathered some pellets from three different locations along the coast from Bettyhill to Tongue to aid a student’s research. After boxing up the pellets, I had a surplus which I laid onto my flower bed in the garden as a kind of nutrient-rich mulch. Months later, in March 2016, as I was weeding the beds, I pulled out a complete pellet and, thinking to myself that I had never analysed the contents of one before, I split it open.

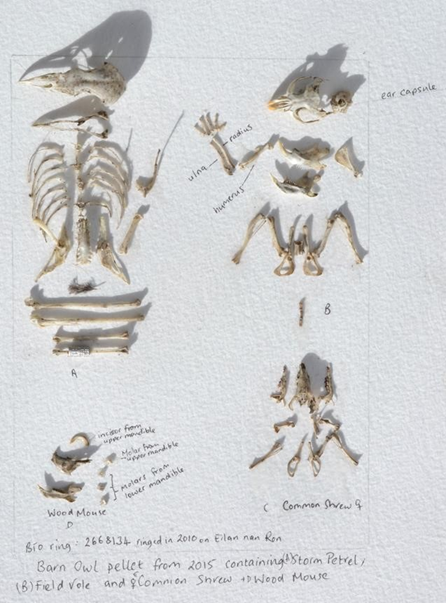

I was astonished to see long bones lined up neatly which I recognised as bird bones, but even more astonished that one of the bones bore a ring. After a little research I found out that the bird was an adult storm petrel Hydrobates pelagicus, which had been caught and ringed on the island Eilean nan Ròn in 2010 during an annual bird ringing expedition. On inspecting the pellet contents, various skulls were found and, using The Analysis of Owl Pellets (Yalden, 2009) and some online information from The Barn Owl Trust, they were identified as those of common shrew Sorex araneus, field vole Microtus agrestis and wood mouse Apodemus sylvaticus.

Barn Owl diets are relatively easy to study because the indigestible parts such as fur, feather and bones are regurgitated in the form of a pellet which is left where the bird roosts. The skulls of prey items are usually complete with teeth which help identify them to species level.

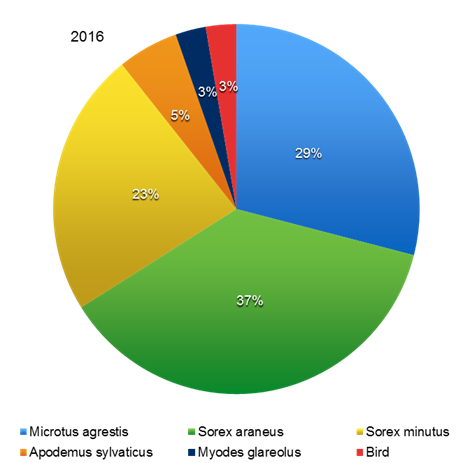

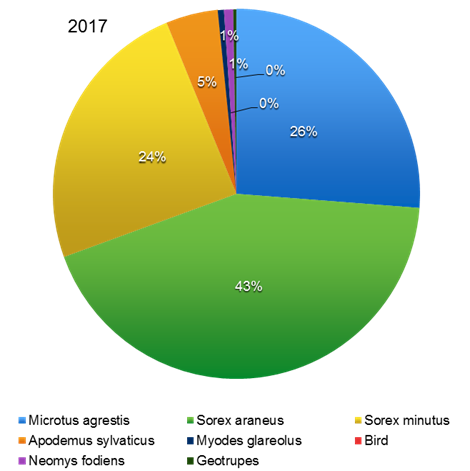

Accumulated pellet data from all Barn Owl nest sites in 2016 and 2017.

Methods.

Pellets were collected (depending on availability) from nest sites at nine locations in eight 10km grid squares (NC54, 55, 63, 65, 66, 74, 75, 76). Given that the barn owls’ home range is around 1km square during the breeding season, this allowed me to localise the resultant records of prey species to a comparable degree of precision. Three to six fresh-looking pellets were collected from each site, put into freezer bags and labelled with date of collection and site. These were frozen to kill off any common clothes moth Tineola bisselliella larvae, which feed on the fur in the pellets, and your woollens and carpets if you release them in the house! Beware, though – freezing does not kill all the larvae.

I dissected the dry pellets using two pairs of forceps and sorted the remains into species. Usually only the skulls and lower jaws were extracted, although unusual bones will be looked at in more detail later. If the numbers of skulls and lower jaw pairs did not tally, the higher one was noted. I found The Analysis of Owl Pellets most useful for aiding identification. Good lighting is essential and I used my binocular low-magnification microscope to see the teeth, although a hand lens would be adequate. The skulls were usually complete, but if the animal was young the bones tend to break up more easily, particularly in Wood Mice. With experience, however, the fragments can be identified. Bird skulls are also delicate and can be difficult to identify to species, although size, bill shape and feathers may give a clue. I found the odd Rabbit bone in a few pellets, which could be the result of the birds eating carrion or, because of the size, needing to break the carcass up into pieces small enough to swallow. Results: The total list of prey species was as follows: field vole Microtus agrestis, bank vole Myodes glareolus, wood mouse Apodemus sylvaticus, common shrew Sorex araneus, pygmy shrew Sorex minutus, water shrew Neomys fodiens, rabbit Oryctolagus cuniculus; birds; a dung beetle Geotrupes sp.

It was interesting, looking at the pie charts for the individual sites, that there was a great variation in the numbers of specific prey items. This could be because of the relative abundance of particular mammals in different habitat types, rather than the owls favouring one type of prey over another. The high number of pygmy shrews from some locations was noteworthy. However, they are reported to be found in extreme habitats such as blanket bogs and mountain tops and do spend less time underground than the common shrew (Couzens et al., 2017, 102-103). Also of note was the absence of brown rats and moles in the pellets compared to the studies by Glue (1967) and Meek et al. (2012). Again, looking at the pie chart figures, there appears to be a local geographical difference in the owls’ diet. Figures published by the Barn Owl Trust have the proportions: field voles 45%, common shrews 20% and wood mice 15%. In comparison, data from our sites, combined over two years (2016 and 2017), show: field voles 26%, common shrews 43%, pygmy shrews 24% and wood mice 5%. The relatively low numbers of field voles, however, may relate to the cyclical nature of their populations, which build up to a peak every 3-4 years.

Conclusions: This study is recognised as being of limited scientific value, due to the low numbers of pellets analysed. However, it has provided some 35 species records of small mammals from the areas around nest sites in eight 10km squares, including sparsely recorded species such as water shrew (Scott, 2011) and includes a number of new 10km square records. Pellet dissection also provides invaluable information on local variations in the prey targeted by the owls, such as the storm petrel from Eilean nan Ròn (Harris, 2016). Acknowledgements: Thanks are due to the following estates for allowing access to their land and buildings: Skelpick and Rhifail Estate, Sutherland Estates, Wildland Ltd., and also to Tilhill Forestry Ltd for access to one of the sites. I am also grateful to Jenny Butterworth for leaving me her owl monitoring records, and to a number of other individuals whose names cannot be mentioned because of the need to keep nest sites confidential. I should like to thank Ian Evans for his helpful comments on an earlier draft of this paper.

References

Couzens, D., Swash, A., Still, R. and Dunn, J., Britain’s Mammals. A field guide to the mammals of Britain and Ireland. WILDGuides. Forrester, R.W., Andrews, I.J., McInerny, C.J., Murray, R.D., McGowan, R.Y., Zonfrillo, B., Betts, M.W., Jardine, D.C. & Grundy, D.S. (eds), 2007. The Birds of Scotland. Aberlady: The Scottish Ornithologists’ Club. Glue, D.E., 1967. Prey taken by the barn owl in England and Wales. Bird Study 14, 200-210. Harris, R., 2016. Barn Owl feeding on Storm Petrels. Scottish Birds, 36(4), 302-303. Meek, R., Burman, P.J., Sparks, T.H., Nowakowski, M. and Burman, N.J., 2012. The use of barn owl Tyto alba pellets to assess population change in small mammals. Bird Study 59, 166-174. Scott, R. (ed.), 2011. Atlas of Highland Land Mammals. Highland Biological Recording Group. Vittery, A., 1997. The Birds of Sutherland. Grantown-on-Spey: Colin Baxter Photography. Yalden, D.W., 2009. The Analysis of Owl Pellets. 4th edition. The Mammal Society. Website https://www.barnowltrust.org.uk

Abby Rhodes was one of the founding members of the wildlife group.

This article was first published in the April 2018 edition of The Highland Naturalist, the in-house magazine for the HBRG. Many thanks to Stephen Moran for making the article available to the wildlife group.

And many thanks to Gary Rhodes for giving permission for Abby’s research to be published on the group’s website.