By Susan Kirkup

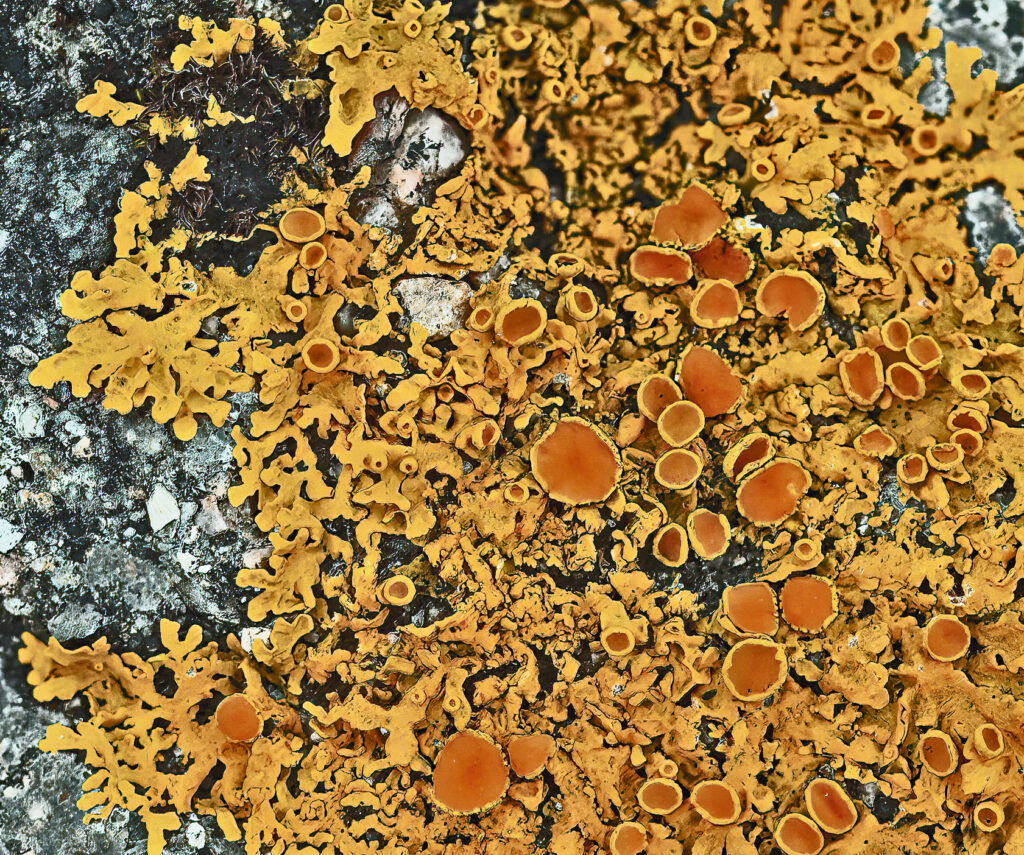

Gaelic name: Crotal (general name).

Lichen is pronounced two ways: ‘like-en’ or ‘litchen’ (as in ‘kitchen’).

What is a Lichen?

A lichen isn’t a plant and it isn’t an animal, it is a composite organism.

Lichens arise from a mutualistic relationship with algae and/or cyanobacteria and multiple fungi species. The fungus forms most of the body of the lichen (thallus) providing a protective layer around the algae. It requires carbohydrate for food, which the algae and cyanobacteria produce and in return they are provided with the sheltered environment they need to survive.

Lichens are non-parasitic and do not harm the plants on which they grow.

Lichens offer food and shelter to a wide variety of organisms, they are excellent at measuring air quality and ecological value, they are beautiful to look at and immensely interesting to study and identify.

Conservation status – many species are common and widespread, some are rare and at risk of decline or extinction. The main threats are, loss of undisturbed habitats and invasive species in woodlands, particularly Rhododendron ponticum.

Distribution – widespread across the globe covering approximately 8% of the earth’s surface. There are approx. 18,000 species worldwide with over 1500 species present in Scotland.

When to look – at any time of the year, so always something to look out for even in the depths of winter. They can be stunning frosted miniature gardens encrusted with ice particles that look like diamonds in the winter sunshine. Get up close and take a good long look, you will be amazed at the detail you see, a magnifying glass or hand lens can be extremely useful to take along with you on your lichen safari.

Where to look – Lichen will grow on just about anything sturdy enough to support them. They can be found on trees, rocks, fenceposts, gravestones and old rotting wood stumps, amongst the heather and mosses on the hills, on soil and in grasses, on shoreline rocks and pebbles, in churchyards and on pavements and walls in villages, towns and cities. Just about everywhere!

Lichens are considered a ‘pioneer species’, able to survive where many other species would fail and are usually the first organisms to succeed in previously uninhabitable areas. Wherever you look, look closely as many of these species are small and can be missed.

What to look for – There are broadly three growth forms to look out for and all of them can be found in North Sutherland:

Fruticose – which have a shrub like branching and bushy habit, often with only one holdfast attachment to the growing substrate.

Foliose – which are leaf-like with a spreading flat loose growth, often with root like hairs on the undersides.

Crustose – crusty, growing very closely and firmly attached to the growing surface, and almost impossible to detach.

Identification Colour and form are important ID features, as are the reproductive fruits produced by certain species. Some species reproduce by fragmentation, pieces of the organisim break off and are dispersed to grow on elsewhere. Others produce ‘soredia’, a mixture of fungal and algal cells resembling tiny powdery or granular fragments. These are dispersed by insects, wind, rain etc.

There are two main types of fruiting bodies.

Podetia, which are found mainly in the cladonia species. These are stalk like or cup shaped (like small golf tees), structures growing from the surface.

Apothecia, which are mainly disc shaped fruits which can be round and resemble jam tarts with the pastry edge or sometimes more oval resembling wine gums. Neither taste anything like those, unfortunately.

Interesting facts:

Lichens have a very slow growth rate with many species growing only 1-2mm annually. Some foliose species can grow up to 1cm per year and crustose species, the slowest growing, often only 0.5mm per year. Crustose lichens are widely studied in respect to dating geographical features and tracking climate change. The age of a lichen growing on an exposed rock face can indicate when the rock was first uncovered, assisting geologists with tracking glacial movements.

The European Space Agency discovered that lichen can survive unprotected in space. Two species of lichen were sealed in a capsule and launched on a Russian Soyuz rocket in 2005. Once in orbit the capsules were opened and the lichen exposed to cosmic radiation and temperatures as low as -20C and up to 20C . After 15 days the lichens were retrieved and were found to be perfectly fine with no apparent damage.

The oldest certain fossil lichen is Early Devonian (about 400 million years old) from the Rhynie Chert, near Aberdeen, Scotland (Taylor et al. 1995).

Possibly the Earth’s oldest organisms are the crustose yellow-green map lichens (Rhizocarpon geographicum) growing in the Arctic and estimated to be 8,600 years old.

Lichens have long been used as a natural pigment for dying cloth and wool. Harris Tweed’s characteristic orange colour was traditionally produced using a dye extracted from rock-dwelling lichens.

Lichen are the main winter food for reindeer.

Lichens provide nesting material for birds and food and shelter to many invertebrates. Woods that are rich in lichens support a varied and important ecosystem.

Certain lichens have varying resistance to pollution which makes them a good bio-indicator, and a natural way of assessing air quality. Where no lichens are present, the air quality is poor. If only crustose lichens are present, the air quality is reasonably okay. If all three types of lichen are present, the air quality is good. We are lucky enough to have all three types here in the North.

All images copyright S.J. Kirkup and S. Kirkup apart from Rhizocarpon geographicum (Wikipedia Commons).

Useful Resources

Books and Guides

The best comprehensive guide in my opinion is Lichens: An Illustrated Guide by Frank Dobson published by RP

FSC produce some excellent fold-out chart guides: Field Studies Council Publication – Lichens.

A fun interactive guide from the Natural History Museum: NHM Lichens ID Guide

Links and Videos

A good introduction. I’ve been observing these on my croft in Scourie, and only just starting to identify some..

I took shelter from the wind in Gleann Einich, Cairngorms against a boulder for 15 mins and was fascinated by the numerous lichen species. This is a wonderful website. Informative and clutter free. As if designed in 2000 but for mobile users!