Sunday 30th April 2023.

By Susan Kirkup

We parked just off the A838 in front of the tall deer gate and stile at the beginning of the track to Arnaboll, where we met our walk leader, lichenologist Nathan Chrismas.

We parked just west of Hope.

Grid reference: NC 46725 59763.

What three words: pastime.salary.shorten

Our walk at Arnaboll was along the west shore of Loch Hope, we would be passing through old woods of birch and hazel, on to the bothy located near the shore . On the way back we would visit the old graveyard on the hill above the bothy. A diverse range of habitats all promising for lichens, and we were to find all three main types: fruticose, foliose and crustose.

Our party of twelve set off on a lovely calm mild morning heading towards the woodland to encounter our first lichens. On the way we spotted newts swimming in a deep puddle on the track, celandine, wood sorrel and violets flowering, and in the woods, a cuckoo was calling.

It wasn’t long before Nathan spotted our first lichens of the day on a cluster of birch trees. The tree branches and twigs were draped with the fruticose lichens Usnea and Ramalina and foliose Parmelia lichens.

Out came the North Sutherland Wildlife Group equipment and we made sure that everyone had a hand lens (loupe) with which to get a closer look at the specimens. Close inspection of the Parmelia revealed soredia on the surface indicating the species as P. sulcata and Nathan talked about how some lichens look very similar and grow together but are a completely different species.

Nathan took a closer look at the Usnea explaining about the white stretchy core within the lichen (similar to knicker elastic), other similar looking lichens do not have this central core.

Moving on down the track we could look out across Loch Hope and were lucky enough to get good views through our binoculars of a black-throated diver in full summer plumage.

Nathan then pointed out to us Lepra amara, the bitter wart lichen, which is found on tree bark. It can be distinguished from other Lepra species by touching the surface with a finger and tasting. A bitter ‘aspirin’ taste will indicate the presence of picrolichenic acid, confirming the species.

Next came Peltigera, often referred to as the dog lichen. The rhizines on the underside of the lichen resemble dog teeth and Nathan explained that according to ancient folklore the species was thought (incorrectly) to be a cure for rabies. There are a number of Peltigera species, the one we looked at was P. membranacea.

Next up was Pannaria rubiginosa with its beautiful chestnut-red coloured apothecia, found by Alex on a piece of birch bark closely followed by Lobaria scrobiculata.

To identify some lichen species it is necessary to chemically test a small area to look for changes in colour. Coming across a recently fallen branch, the lichens of which would have a limited lifespan, Nathan took the opportunity to demonstrate the method of testing.

At this point of the walk we were in amongst the old birch and hazel trees. The microclimate of this particular area is very reminiscent of the west coast, where the more humid and warmer climate has facilitated the establishment of the rather special Atlantic Rainforest habitat. The most obvious proof that this is similar habitat was the wonderful tree lungwort (Lobaria pulmonaria) growing on the hazel trees. There’s more information on this important habitat at Temperate Rainforest.

The path now led out of the woods and onto the rocky shore of Loch Hope, which we followed for a short way, looking at crustose lichens on the rocks and found some good examples of Rhizocarpon geographicum (the map lichen) and Ophioparma ventosa (the blood spot lichen).

We then crossed a grassy field, covered in drinker moth larvae, heading towards the nearby bothy. As the bothy was occupied, we decided to have lunch on the loch shore.

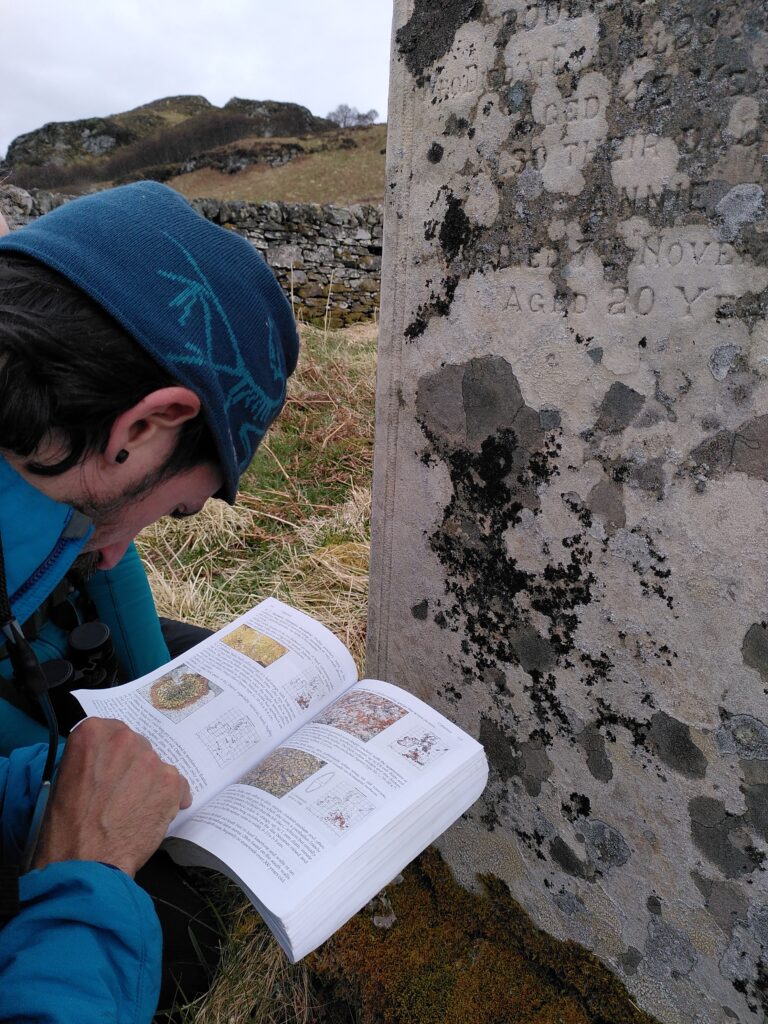

After lunch we climbed the short hillside to the old Arnaboll graveyard where we looked at various crustose lichens on the old stone walls and headstones. Cemeteries are excellent places in which to find a range of lichen, particularly of the crustose type. The different types of stone used in the walls and on headstones gives rise to a variety of species. Indeed graveyards have been valuable in establishing the age of lichens, and the rate at which they grow. Headstones are pieces of rock with a date on them, giving naturalists a good indication of the age of any lichens growing on the surface. Here’s a video about measuring lichen growth on headstones.

Nathan pointed out some bright orange Caloplaca sp. on the stone walls surrounding the cemetery, and Ochrolechia parella (the crab eye lichen) on the gravestones.

This turned crimson, indicating a Caloplaca sp.

© Aurore Whitworth

With our lichen discoveries at an end and the weather starting to turn to rain we set off back towards the track and on to the car park.

On the way back we came across a small flock of redpoll in a group of birch, and wheatears were to be seen on the crags. And amongst the early flowering wood sorrel was an unusual pink bloom.

An immensely informative and interesting talk and walk, enjoyed by all of us. Nathan was not just spotting and identifying lichen species, but he also took time to explain the origins, evolution and life of lichens, as well as how and where they grow. Emphasising the importance of the temperate rainforest sites we have, he gave us an interesting insight into this captivating subject, inspiring us to look closer and learn more about the lichens on our part of the planet.

A big thank you to Nathan, and also to Kat for helping us out with the spellings!

More information on lichens can be found on our website at: An Introduction to Lichens by Susan Kirkup

A list of other species recorded on the day:

Lecidella sp.

Pertusaria pertusa (pepperpot lichen)

Usnea florida

Ionaspis lacustris

Ochrolechia androgyna

Dermatocarpon luridium

All images copyright: Susan Kirkup, Stephen Kirkup unless otherwise stated.