Ian Evans and Stephen Moran

Members of the Highland Biological Recording group (HBRG) visited two contrasting islands off Skerray on the north coast of Sutherland last summer as contributions to the final season’s recording for the Botanical Society of Britain & Ireland (BSBI)’s Atlas 2020.

Neave or Coomb Island (NC6664).

On the sunny morning of 18 July 2019, Ian Evans, Gwen Richards and Stephen Moran crossed the short distance from Skerray Harbour to this island, in a small boat piloted by Mrs Jean Maclean of Borgie, accompanied by three of her grandchildren.

The island is some 30 ha in area and rises to 70m (231ft) at its highest point. Its fractured rocks, part of the Moine Series, make for rugged seacliffs round its perimeter, apart from a sandy bay, Port Gaineamheach, on the southern side. There are the remains of an ancient ‘chapel’ just to the west of the bay (Coomb is a contraction of Columba), but no other signs of habitation. It has not been grazed in living memory.

The landing beach is backed by dunes which morph into grassland at the base of inland cliffs on two sides. The grassland sward, dominated by tall oat-grass Arrhenatherum elatius, is very thick in places, a bit like walking on a bulgy mattress. In broken ground at the base of the cliffs a good variety of tall herbs appear, including greater knapweed Centaurea scabiosa and field scabious Knautia arvensis; there are also bushes of a white-flowered rose. Lack of grazing has also allowed the prostrate juniper characteristic of the north coast, Juniperus communis nana, to develop into thick hanging swags.

Striking components of the cliff-top vegetation were huge plants of Scots lovage Ligusticum scoticum. This succulent umbellifer is normally confined to inaccessible scree and rock faces in its coastal habitats; on Neave it grows like garden angelica.

Gwen had a good range of species in shorter grassland higher on the island, including many sites for spring squill Scilla verna, a typical northern coastal species. She also encountered some rugged areas of cliff scenery. The total number of higher plants recorded was 106 species.

Stephen’s efforts with the D-vac yielded a good variety of spiders and molluscs. The former, which Ian identified, included a number of species apparently ‘new’ to the north coast: a ground spider Zelotes cf. latreillei, crab spider Xysticus erraticus, jumping spider Euophrys cf. frontalis, and a comb-footed spider Phylloneta impressa. Those marked cf. were immatures, but have been included to alert future naturalists to their probable presence. The molluscs were kindly identified by Dr Adrian Sumner of the Conchological Society. Amongst the 10 species present were two tiny ones (c. 2mm.) of especial interest, the ribbed grass snail Vallonia costata (possibly the easternmost record on the north coast) and the striated whorl snail Vertigo substriata.

Stephen reported that his insect catches (60-70 species in all) included 21 bugs, of which there were three species new to him, the leafhoppers, Anaceratagallia laevis, Hyledelphax elegantula and a Macropsis (cf. impura, which couldn’t be confirmed from the female found). The beetles encountered included the leaf beetle, Galeruca tanaceti (2nd VC record; Keith Alexander found it at Portskerra in 2018), seven and eleven-spot ladybirds and the tiny Pselaphid, Bryaxis puncticollis. The coastal weevil Philopedon plagiatus was much in evidence on the seaward edge of the dunes where several pairs were observed mating and experiencing considerable difficulty maintaining their balance in the soft sand. Three species of snail-killing fly, Sciomyzidae, were seen; perhaps not surprising given the thriving mollusc population of the island. There were also sightings of the disctinctive sawfly Cladius pectinicornis and the ants (identified by Murdo Macdonald), Formica lemani, Myrmica lobicornis and M. scabrinodis, the two Myrmicas being first records for NC66. The mottled grasshopper, Myrmeleotettix maculatus, was everywhere in the small dune system.

Perhaps the ‘star’ insect found was the small ground-dwelling lacewing Psectra diptera, a third record for this hectad in four years. This rather hard-to-detect species was seen on the Rabbit islands in 2016 and at Coldbackie in 2017. Also of interest was the small grassland-dwelling barkfly, Kolbia quisquiliarum, the record based on an already dead specimen swept from field scabious over scree.

The three of us also logged seven species of butterflies: meadow brown, small heath, small tortoiseshell, common blue, green-veined white, small pearl-bordered and dark green fritillaries, and Gwen had several yellow shell moths Camptogramma bilineata with the dark brown markings approaching those of ssp. hibernica, which are a feature of north coast populations.

After a very enjoyable four hours on the island we were collected by Mrs Maclean and returned to the mainland, where her grandson Harry requested and was given some training in the use of the D-vac, in the course of which he turned up what is probably the most northerly record by some distance of the weevil, Leiosoma deflexum.

Eilean nan Ron (island of the seals).

Our second island visit, on 5 August 2019, was rather more challenging. This time we were taken across by Jean’s son Andrew Maclean, accompanied by two of his children. The group of four islands, with an area of 138 hectares, lies about 2m north-west of Skerray. Only the main one (NC6365) is readily accessible, by a pier on the eastern side, from which there was once a steep flight of concrete steps with an iron hand-rail up to a ridge, and then onto level ground. Unfortunately the upper part of the steps have gone and the rail is unsupported in places, so access now involves a scramble up a slightly ‘airy’ section of the cliff.

Former cultivated land covers much of the ‘neck’ of the main island, which rises to an altitude of 76m (249 ft) at Cnoc an Longein in the north-west, and to 75 m (246ft) at Cnoc na Caillich in the north-eastern corner. Much of the coast consists of precipitous cliffs, with some spectacular gullies, caves and natural arches (Figure 11) carved out of the sandstones/conglomerates, supposedly of Devonian age, of which the islands are formed.

The main island was last permanently inhabited in 1938 and the ruins of some 16 houses still stand, four with roofs more or less intact. It is inhabited by a flock of perhaps 100 feral Hebridean sheep, which, owing to the deterioration of the access steps, have now been left to their own devices for a considerable time. It is therefore quite heavily grazed. This, combined with the effects of exposure, is reflected in the short shrubby vegetation covering higher parts of the island, dominated by bearberry Arctostaphylos uva-ursi, crowberry Empetrum nigrum and creeping willow Salix repens.

The party on this occasion was five. Stephen concentrated his entomological efforts on the site of the former village and cliffs adjacent to the landing place. Gordon Rothero and Ro Scott recorded bryophytes and higher plants in the eastern part of the main island (NC6465/6466), and Gwen and Ian, accompanied by Jess, recorded the western part (NC6365).

The botanical diversity was less striking than on Neave Island, but a grand total of some 140 species were recorded from the two main monads. Ro and Gordon also recorded ten species from a tiny sliver of land in an adjacent monad (NC6466) on the northern coast. Their most interesting discoveries were some 150 rosettes of Scottish primrose Primula scotica in coastal turf, and the tiny annual allseed Radiola linoides on the cliffs above the small bay adjacent to the steps. Gordon recorded 56 species of bryophytes, a good number given the degree of exposure; he described them as all ‘typical north coast species’.

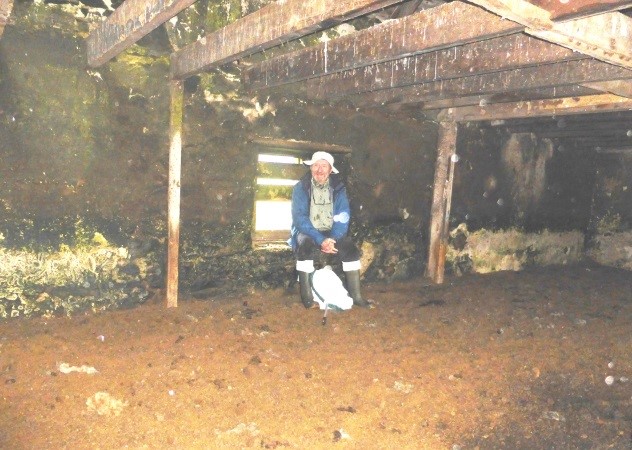

We enjoyed good weather and stunning views of the north coast for much of our five hour visit, but early in the afternoon dark thunderclouds approached from the south-west, which delivered a short but sharp downpour, during which we all took refuge in two of the houses still boasting roofs. Since there was sheep dung almost up to the level of the mantelpieces, this entailed perching on windowsills; the sheep also tried to take shelter, but were spooked by our presence.

Larger animal life included a variety of birds, including great skua, fulmar, storm petrel, common snipe, wheatear, rock pipit, wren and starling and six species of butterflies, meadow brown, common blue, painted lady (larvae on thistle and adults), scotch argus and the larvae of red admiral and peacock on nettles.

Stephen found the close-grazed swards, predictably, rather less productive than those on Neave Island. On rushes there were the larval cases of the micro-moth, Coleophora alticolella, and sweeping the same area produced the large distinctive cranefly, Pedicia rivosa and the handsome hoverfly, Eristalis intricarius.. The bug population was distinctly impoverished, but other areas of the island might be more productive on another occasion. A look at some gorse, beyond the village produced the only lacewing seen all day, one of the large green species in the Chrysoperla carnea group – separable on song or DNA, however the equipment for either analysis was not to hand! Also on the gorse was the micro-moth, Mirificarma mulinella, observed at the point which the heavens opened and brought play to a close. Whilst waiting on the landing stage for the return boat we were able to observe from directly above the swimming skills of a barrel jellyfish, Rhizostoma pulmo.

It was a privilege to be able to visit two islands with such contrasting histories. We would like to record our special thanks to the Maclean family for ferrying us and for their interested company.

This article was first published in the May 2020 edition of The Highland Naturalist, the in-house magazine for the HBRG. Many thanks to Stephen Moran for making the article available to the wildlife group.