Latin name: Bombus distinguendus

Gaelic: Seillean Mòr Buidhe

By Sarah Bird, Project Officer, Species on the Edge, North Scotland Coast, working for Plantlife

The iconic Great yellow bumblebee is very scarce in the UK today. It used to be found all over Britain, but has been lost from most of its former range, and is now only seen along coasts and islands of north of and west of Scotland. It is a Species on the Edge Priority Species in 4 regions: Orkney, North Coast, Argyll Coast and Inner Hebrides, and Outer Hebrides.

Remaining populations in Scotland are threatened too; they are small and fragmented, and the bumblebee’s habitat is disappearing.

Where to look

Great yellows need lots of flowers from June through to September. They are found in machair grasslands, wildflower meadows and occasionally in gardens. Along the north coast it is also worth watching for them along road verges, and in carparks and campsites where there are lots of flowers. The carpark and garden at Castlehill Heritage Centre in Caithness, and the meadow at Farr Glebe near Bettyhill, are good places to look.

When to look

Great Yellow bumblebee queens emerge from hibernation from mid-May onwards, and they are active up to the end of September or early October. They are most active during warm, sunny days in summer when conditions are not too windy.

Nests are generally active for about 4 months. Workers appear roughly 6 weeks after the nest is established – around July, and new queens and males are produced towards the end of the active period.

What to look out for

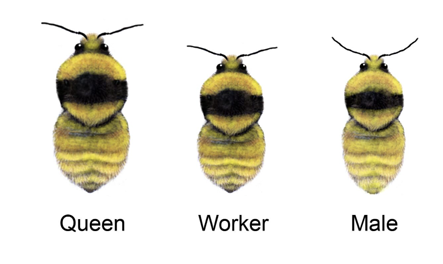

The Great yellow bumblebee is reasonably easy to recognise. It helps that all three castes (queens, workers and males) are similar, and they are quite large. The thorax is bright golden-yellow with a black band between the wings; the abdomen is all yellow, with no distinct tail. Queens: 19-22mm long Workers: 10-18mm long Males: 10-18mm long

Great Yellow Bumblebee markings © Bumblebee Conservation Trust

The only species that could be confused with Great yellows are the Common carder bumblebee (Bombus pascuorum) and Moss carder bumblebee (Bombus muscorum), but they are more ginger in colour and don’t have a black band on the thorax.

Life Cycle

In late summer/autumn mated queens find hibernation sites under grass tussocks in sand dunes or soil. They hibernate through the winter and spring, emerging in May or June the following year. They then feed, start a new nest, and lay eggs there. The first eggs hatch into larvae which develop into worker bees and the colony grows until late summer. Nests of Great Yellow bumblebees are hard to find, but they often use old rodent burrows in areas of tussocky, taller grasses. Colonies are quite small, with between 30 and 80 workers. The eggs laid by the queen late in the summer develop into males and new queens. These emerge in August and September and mating takes place. In autumn the old queen, workers and males all die, and the new queens hibernate. Queen Great yellow bumblebees may live for a year, but workers and males only live 2-6 weeks.

Threats

Habitat loss is the biggest threat to Great yellow bumblebees. “Since the 1930s, over 97% of wildflower meadows have been lost. Where once thirty species of plants would bloom under your outstretched arms, in most of our fields there are now just six.” (Source: Plantlife Meadows Hub)

There are lots of activities that have acted together to contribute to this huge loss of habitat – some are:

- Mowing of verges, parks and green spaces

- Changes in farming practices to supply our food – especially the move away from hay production to making silage

- Climate change

- Abandonment of smaller farms and crofts due to increasing economic pressure.

Species on the Edge and conservation partners are working with farmers, crofters and land managers to advise on best management and targeted work to benefit the Great yellow bumblebee.

What can you do?

1. Record Great yellow bumblebees

The Great yellow is now one of the two rarest bumblebees in the UK, and every sighting is important. Please record every Great yellow bumblebee you see! You can do that here, or by posting on our facebook group. When you send in a record of Great yellow bumblebee please add the name of the flower it was visiting if you know it – thank you!

Experts at the Bumblebee Conservation Trust (BBCT) need help to study the health of Great yellow populations and find out more about the reasons for their continued decline. They know where the remaining populations are, but not how big those populations are – so your records will make a difference.

If you are really interested in bumblebees you can join us on a BeeWalk each month in Thurso, Durness or Kinlochbervie. Please get in touch with me: sarah.bird@plantlife.org.uk

2. Grow Flowers for Great yellow bumblebees

Great yellows need flowers – LOTS of flowers all the way from May to September/October. They particularly need flowers that bloom late into autumn in order to complete their annual lifecycle. A nest that does not produce new queens and males in late summer has failed, so a supply of nectar well into September/October is essential.

You can help by encouraging wildflowers in your garden or local community green spaces, and by growing their favourite plants in gardens too.

Wildflowers

Great yellows have a long tongue, and can feed on deep flowers where the nectar is out of reach of some other insects. Wild flowers they particularly love are knapweeds, red clover, vetches, comfrey, field scabious, devils-bit scabious and bird’s foot trefoil.

Wildflowers and garden plants in the pea, thistle, and mint families are useful too.

Garden plants

In a new review BBCT has made a list of the garden plants that GYB have been known to use. The top choices are listed below. The best thing to do is grow lots of the same plant in a cluster, so that the bees have plenty of food in one place and don’t have to use too much energy flying between plants or gardens.

Chives Allium schoenoprasum

Columbine Aquilegia vulgaris

Borage Borago officinalis

Pinks Caryophyllaceae spp.

Cornflower Centaurea cyanus

Perennial cornflower Centaurea montana

Globe thistle Echinops sp

Viper’s bugloss Echium plantagineum

Redclaws Escallonia

Fuschia Fuscia sp.

Geranium Geranium sp

Hebe Hebe sp

Sunflower Helianthus sp.

Common Bluebell Hyacynthoides non-scripta

Hooker’s fleabane Inula hookeri

Poached egg plant Limnanthes sp.

HonestyLunaria annua

Lupin Lupinus sp.

PoppyPapaver sp

Pyrancatha Pyracantha sp

Stonecrop Sedum sp

Weigela Weigela sp.

Wisteria Wisteria sp

Note: Avoid invasive non-native species such as Cotoneaster horizontalis, and Rhododendrons as they often escape from gardens and can damage wild habitats by displacing native species.

Finally – Fascinating Facts

Did you know that bumblebees have smelly feet? Foraging bees leave a scent on flowers they have just visited, and other bumblebees detect this. This helps them know which flowers have recently been drained of nectar and are not worth visiting.

The bright colour bands that we use to identify bumblebees are only on their hair. If you saw a bee that had been shaved of all its hair, you’d be left with a black shiny flying insect (please DON’T shave a bumblebee to find out!).

Further information